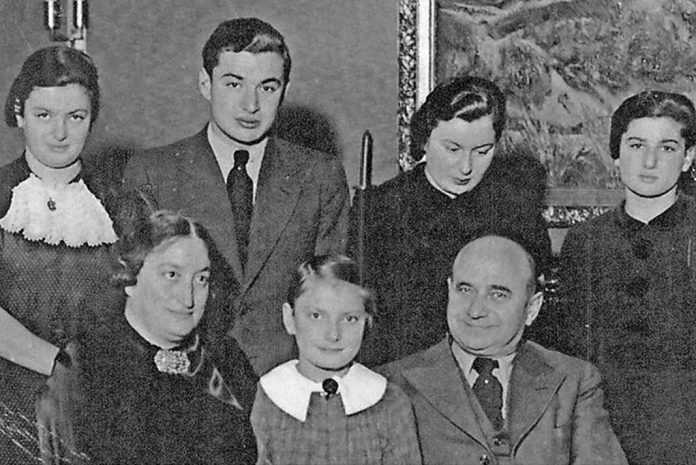

The last photo taken of the whole Cohn, Bucky and Levy family together, before the two older Levy siblings left to work in Port Elizabeth.

When last did you hear of a German town that stages a play recounting the lives and deaths of its most well-known Jewish residents in the Holocaust? This is exactly what has happened in the town of Altenburg, Germany in May 2017, where sold-out shows depicted the story of the Cohn, Bucky and Levy families, who went from prosperous business owners to murdered refugees in Auschwitz.

The Cape Town Jewish community has a direct link to this history, as Cape Town locals Michael and David Liebrecht are the second-generation survivors of this family. Indeed, it is not often that a family are invited to a German town, hosted by its officials and shown a play about their family’s history, but this is exactly what the Liebrecht brothers did this past May. It all started when Altenburg’s official historian, Christian Repkewitz, began looking into the history of the Jewish family that owned 12 properties in the town, who became refugees and were killed in the Holocaust, and who had left an impact on the village’s businesses, arts and culture and history.

Only three family members survived because they had moved to South Africa after the family fled to Holland. The Liebrecht’s brothers’ mother, Lotte Liebrecht (nee Lotte Levy), survived because she stayed on in South Africa to learn English after visiting her two elder siblings Hans and Ruth, who had gone to Port Elizabeth to live and work. Her twin sister Lore and her entire family returned to Holland, where they had made a home after fleeing Germany. Believing they would be safe in the Netherlands, they were all deported and murdered at Auschwitz. Lotte went on to marry in South Africa and had her son Peter Rawaray from her first marriage.

In his book about the family’s history, Repkewitz writes, “It is no exaggeration to claim that for decades the most influential and renowned Jewish citizens of Altenburg were members of the Cohn, Bucky and Levy families. Thanks to their exceptional commitment to civic, social and cultural causes, the Cohns, Buckys and Levys were acknowledged by and popular with the council and general population alike. In light of this popularity, the process of marginalisation, hostility and eventual persecution seems even more incomprehensible.”

His book explores how the family — which owned a 30-room house, 12 buildings in a town, numerous businesses, who were involved in the theatre, had the Iron Cross and were reputed all over Germany became victims of the Nazis. This story is a microcosm of the Holocaust, and Repkewitz understood this. He first contacted the Liebrecht brothers in 2015, to say he was laying Stolpersteine (‘stumbling stones’, which are placed as memorials outside the homes of Jews murdered in the Holocaust) at the family home in Altenburg. They had never heard of this man who had meticulously researched and recorded their family history, but they quickly became close friends.

The brothers travelled to Altenberg for the laying of the Stolpersteine, where they met Repkewitz and the mayor of the town, as well as relatives from London, Canada and the USA. They saw where their mother had grown up, and the magnificent home and street which had been named in honour of the family.

But this was not the end of Repkewitz’ work. A passionate historian who refuses to leave the past buried, he produced his book and a theatre script, and the town raised funds for a play to be produced about the Jews who had once lived there. With the support of the German government, the play became a reality, and the actors were Israeli, Palestinian and German. “For me, this was absolutely wonderful, as it shows the meaning of history,” says David. If Israelis and Palestinians can act together in a play about the Holocaust, perhaps its lessons are not lost.

He explains that at first, the actors did not get along, but by the end of the time together they were like brothers. And when the play was finally performed for the family, there was not a dry eye in the audience or on stage, as all the actors, producers and family members shared a moment of healing together. David feels that bringing together actors from a conflict zone was what his mother would have wanted, as she was always concerned with uplifting others.

As the family was welcomed to Altenburg, banners and posters advertising the play filled the streets, and the show was sold out immediately. “The locals got to know us and were extremely welcoming. They were taking responsibility for their history,” says David. At a special dinner that he hosted for the family, the mayor of the town asked for forgiveness from the second generation.

This was no ordinary play — it was a “moving play,” where the audience walks with the actors to watch scenes performed around the village of Altenburg. Michael and David’s grandfather, Albert Levy, had been the Patron of the magnificent local theatre, and the family’s connection to the arts is strong. In fact, when the family was banned from attending shows because they were Jewish, the musicians and actors would risk their lives by performing late at night at the house.

While the producers of the play had access to this theatre (which has not changed since the war), they chose to rather perform the play ‘on the streets’, hitting much closer to home and showing that so much happened in this very place, where neighbours turned upon neighbours and anti-Semitism meant exclusion from every aspect of daily life.

David describes some of the scenes, which delved into the family’s history: We see the three Cohn sisters in front of their successful department store, and the births of their children are cleverly performed. The audience then walks through an empty house and in each room we see the family’s story in action.

For example, we watch Albert Levy opening and closing a locker, and as he repeats this motion he talks about being arrested and taken to Buchenwald, which left him a broken man. We see Lotte and her twin sister Lore playing happily, during an innocent childhood that was stolen from them. The family’s beloved library is beautifully recreated, but later there is a harrowing scene of the Nazis throwing the books into a fire. This library was Franziska (Bucky) Levy’s greatest joy, and she was arrested by the Gestapo for communicating with famed authors like Thomas Mann.

As the audience walks through the damp, dark house, they can hear actors shouting ‘kill the Jews’ and ‘burn the store’ from outside. The final scene depicts the family members standing silently, each with a pile of clothes in front of them. For those murdered by the Nazis, a stone rests on their clothes.

Watching their family history come alive was extremely emotional for the Liebrecht brothers, and David describes it as one of the most amazing experiences of his life. The play is now travelling to Israel and America, and the brothers would love to see it performed in South Africa as a school play or a theatre production. They also hope that other towns across Europe will take on such a project, exploring their Holocaust history through the arts. “These are stories that need to be told,” they conclude.

I believe that my father was a nephew of Albert Levy. I knew Henner,Ruth and Lottie growing up in Port Elizabeth. They were the only family my father had left.

Would like to contact the Liebrecht brothers.

I emigrated to the States in 1974.

Hi Judith send me your contact details and I will pass on to David and Michael whom are my uncles