|

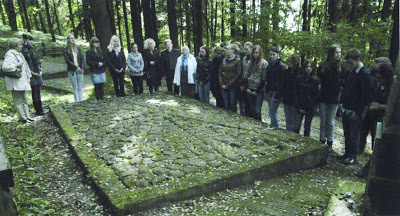

| Students from the Tolerance Centre at the mass graves. |

Former Capetonians Abel and Glenda Levitt have been working for over a decade in the town of Plungyan to preserve the memory of the Holocaust in Lithuania. They tell us about their work and their current project to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the genocide.

“Plungyan was the birthplace of my father, and was where his mother, brothers and sisters were killed in the Holocaust,” explains Abel Levitt. But like most other South African Jews, he had not been to this place of heritage and history. It was only in 1998, when their son, Adam, was sent to play a rugby match in Lithuania for the Israeli rugby team, that Abel and Glenda investigated visiting the country. It was this catalyst that took them on a journey of discovery, work and education that touched the very heart of South African Jewish heritage in Lithuania.

Mendel Kaplan, one of the few South African Jews who had visited Lithuania before 1998, told the Levitts there was one Jew remaining in Plungyan — Jakovas Bunka. Abel called him, and in limited Yiddish explained why he wanted to come to Plungyan. As they spoke, Bunka told him to wait while he looked in his exercise book, where he had recorded the names of Jewish families who had lived in Plungyan before the Holocaust.

When Bunka returned from the war, he went round the town and wrote down the names of the people who had lived there. He came to 700 names. “We know from official records that 1800 Jews had been murdered,” explains Abel. Bunka found the name Levitt in the book, along with the names of family members who had been killed. When they arrived in Lithuania, Bunka’s son, Eugenijes, took the Levitts to the mass graves in the Kaushan forest outside Plungyan, “which are regarded by some people as one of the ten most important Holocaust sites in Eastern Europe,” explains Glenda.

Like so many other communities in Eastern Europe that were decimated by the Einstazgruppen, the Jews of Plunyan were rounded up and locked in the Groyse Shul (Great Synagogue) for two weeks. On 15 July 1941, the entire community was taken to the nearby forest, where they were shot and buried in six mass graves.

A centre of tolerance

Following their first visit, the Levitts organised a trip to Plungyan for 43 members of their family, to coincide with the 60th anniversary commemoration of the Holocaust in Lithuania. Every year, on the third Sunday of July, a memorial meeting is held in the forest. While there is only one Jew, many local and national Lithuanians attend the event. “As we left that meeting, Bunka said that the mass graves aren’t protected, and that he is finding it difficult to maintain them.” He asked the Levitts if they could raise money to have the mass graves covered properly. Abel spoke to the family members at that event, and together they raised enough money to cover the graves with cobbled stones — symbolising the stones of memory placed on Jewish graves.

But the Levitts’ journey was not over yet. A number of Lithuanians spoke at the memorial service, and one who made an impression on them was a teacher by the name of Danute Sarapiniene, who spoke emotionally about the murder of the Jews and how this was a loss to the Lithuanian people. The Levitts learnt that since 1995, Danute had been conducting lessons about the Holocaust at her high school in Plungyan without any financial support. She had finally been given permission from her headmaster to conduct these Holocaust lessons in two small classrooms, but they were in state of disrepair.

The Levitts had funds left over from their first initiative, and therefore decided to establish a ‘Tolerance

Centre’ in Plungyan, to be run by Danute. These centres are a little-known phenomenon across Lithuania. They are for students and youth, and educate about the Holocaust.

Art and investigation

“That Tolerance Centre has been a great success. We send students and teachers on tours with Jewish guides; they keep the site of the mass graves clean; and on events such as UN Holocaust Day they hold a ceremony,” explains Abel.

One of the visitors the Levitts took to the centre was Sir Ronald Harwood. He had just won the Oscar for The Pianist, and his father was born in Plungyan. In honour of his visit, the Levitts established the Ronald Harwood prize for work on the Holocaust in the arts.

The competition is held every year by the Tolerance Centre for the youth of Plungyan to create works of art that commemorate the Holocaust. “The work is so vibrant and exciting, and their interpretation, sincerity and empathy are amazing. One year they gave us the first, second and third prize pieces, which we gave to Yad Vashem,” says Glenda.

In addition, the centre took its members on a trip to an area near Plungyan, where the students interviewed older people about their recollections of the Holocaust.

A wall of names

Meanwhile, Abel explains that when they went to Plungyan in 2001, the old shul was still standing, but that it was in a state of disrepair. The shul was eventually given to the Plungyan Jewish society, who decided to sell the dilapidated building, put the money into a charity fund and demolish the shul. Meanwhile there was some opposition to demolition of the building; it was in danger of collapsing, was in a run-down area, and “What do you do with place that can’t be used? It would be an empty memorial,” says Glenda.

The Levitts were in Plunyan when the shul was demolished, and organised that the bricks were saved, which they realised could be used in the future. This takes us to their current project. As mentioned, Bunka had collected 700 names of Jews from Plungyan. Now, Glenda and others did further research to add to the list. Together they came to 1200 names.

Ultimately, they had this list, and the bricks from the shul. The 1800 Jews of Plunyan did not have gravestones, and thus the Levitts decided to build a wall of 1800 bricks from the shul to commemorate the dead. There would be plaques listing the 1200 names, and explanations of what happened to the Jews of Plungyan.

On 17 July the wall of names will be consecrated, followed by a memorial ceremony marking 70 years since the Holocaust in Lithuania. The Levitts hope that South African Jews will join them in commemorating our history.

Fragile connections

The Levitts say that if there is any similarity to South African Jewry in Lithuania, it is merely an echo. 94% of Jews were killed in Lithuania, and with the draconian Soviet occupation, poverty and small numbers, the Jewish community is a shadow of what it once was. But at the same time, there are shuls, Jewish day schools and welfare programmes in the bigger cities. “And the names!” says Glenda. In cemeteries you see familiar names, and even their list of names is like “A Herzlia parents list!” In addition, Glenda often comes across food in a supermarket in Lithuania that she thought was distinctive to Cape Town, and “the food we grew up with” is similar to Lithuanian food.

The Levitts understand that travel, costs and the lack of concrete memorials to the Holocaust have hindered South African Jews from travelling to Lithuania, but feel that engaging with this history in a variety of ways is vital — for example, ‘twinning’ with students in Plungyan would allow those children to see a thriving Jewish community with roots in Lithuania, and Capetonian Jewish children would connect to their own heritage.

Ultimately, what motivates the Levitts to do this work? More Lithuanians than Germans killed Jews in Lithuania during the Holocaust, and “I understand when people say ‘I don’t want to go there.’ But our view is different: we mourn what happened, but to ensure that it never happens again, we need to establish education,” says Abel.

Glenda adds: “Our motivation is firstly to honour those who were murdered, and secondly, to assist in educating people to abhor hatred and racialism of any kind. We want to honour the past and look to the future. We weren’t interested in doing one without the other.”