|

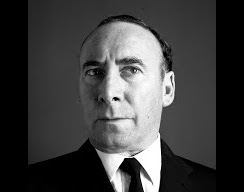

| Sir Antony Sher as Phillip Gellburg in ‘Broken Glass’. photo: Jesse Kramer |

In this exclusive interview with Sir Antony Sher, the esteemed actor discusses his Jewish and South African identity, his latest play showing at the Fugard Theatre, and why Sea Point still feels like home. What are some of your most enduring memories of growing up in Cape Town, and how has that period influenced the rest of your life?

My most enduring memory of growing up in Sea Point is of the sea itself. It makes the whole place look blue. And there’s that smell in the air, of salt and kelp. And the sound of the waves, gentle in summer, like thunderclaps in winter. These are very intense sense memories, and makes Cape Town ‘home’ for me in a more vivid way than those locations in England, like London and Stratfordupon- Avon, where I’ve actually spent much more of my life. The other thing about my childhood was growing up under apartheid. I think all of us who experienced that, whether black or white, learned some profound lessons about human beings, and they’re not comfortable ones. We lived through one of the major atrocities of the 20th century. The way it has influenced me is that the theme of persecution runs through a lot of my work both as an actor and writer. The persecuted and the persecutors, and how one can turn into the other — these are characters to which I’m powerfully drawn.

In comparison, what are your thoughts on the Cape Town Jewish community today?

As a secular Jew I don’t have much contact with the Jewish community here (apart from my family), but I am aware that they’ve been very supportive of the shows I’ve performed in Cape Town, and I’m grateful for that.

You have performed in Primo, God on Trial and now Broken Glass. How does your Judaism inspire, motivate or challenge you in these roles?

I wasted a lot of time in my youth trying to deny the primary aspects of my identity: being Jewish, being gay, and being a white South African. I ended up in so many closets I didn’t know which key was which. It was absurd — you can’t not be who you are. Since I’ve ‘come out’ about myself, and learned to celebrate all the aspects of my identity, it’s particularly satisfying playing Jews, gays or South Africans. Gellburg in Broken Glass is especially interesting since he is wrestling with his own identity, and could be described as a self-hating Jew.

Your connection to South Africa has remained strong, with an Africanised production of The Tempest, your documentary Murder Most Foul, and your numerous visits to perform in the country. These demonstrate both a love of and a struggle with South Africa. What is your perspective of the country today, in this context?

I’m pleased that my career has expanded to include regular work in my homeland. It feels like things have come full circle. But yes there is both love and struggle in my feelings for South Africa. The statistics for violent crime shock me senseless. And when in 2006 the young actor Brett Goldin was murdered, it prompted me to join forces with a fellow Jewish South African, the documentary film-maker Jon Blair, to make Murder Most Foul, which looked at the whole issue of violent crime in this country. There are times when you can learn too much about certain things, and what I learned on that film has left me unsettled. I notice that whenever my partner Greg and I come home to see the family, I’m more nervous travelling around Cape Town than I used to be.

Tell us about Broken Glass, and why you think the Cape Town Jewish community would find the show particularly relevant?

Arthur Miller has fashioned a brilliant structure for Broken Glass. It is set in November 1938, the time of Kristallnacht in Germany, but the actual location of the play is Brooklyn, New York, where we watch members of the Jewish community react to the news from Europe. One character is traumatised — it’s almost as if she has a premonition of the horrors to come. Another character thinks it will all blow over; he has studied in Germany, he likes the people, admires their music and literature, and can’t believe that they’re capable of extreme brutality. And then there’s my character, Gellburg, with his own problems about being Jewish, and his need to serve his non-Jewish boss, who practises a subtle form of antisemitism. I think there’s a lot that a Jewish audience will recognise as familiar. The play is moving and funny too — Miller is very good at finding laughter in the darkness.

How do you feel about performing at the Fugard Theatre, in the context of Fugard’s role in South African theatre?

I’m very honoured to be performing at the Fugard. I think its creation is one of the best things to happen to South African theatre in a long time. It’s a beautiful building — the auditorium, the foyer, even the rehearsal room! And the plans for its future, which were outlined to me by its founding producer, Eric Abraham, sound very exciting. It goes without saying that Athol Fugard himself is one of the greats of South African theatre. He’s also one of my personal heroes. Before I left South Africa, and while still in my teens, I saw the original production of Hello and Goodbye (in which Fugard played Johnnie) and it changed my life. I had no idea that drama could be as raw and real as that. Years later, in 1988, the Royal Shakespeare Company brought over Janice Honeyman (who is directing Broken Glass and also did The Tempest) to direct me and the South African actress Estelle Kohler in Hello and Goodbye. Talk about things coming full circle. It was one of the most fulfilling experiences of my career.

What would you say to young South Africans who want to make it in the acting world?

It is a rough, tough, cruel profession. Everyone goes into it wanting to be a star, but that will only happen to a tiny, tiny percentage. Which means a lot of disappointment for the rest. Most actors are definitely going to undergo rejection and unemployment. This will feel very hurtful because the product you’re trying to sell is yourself — your face, your voice, your talent — and people don’t always want to buy it. It’s important to tell this to would-be actors. If they hear and believe these harsh facts, and then still want to proceed, then maybe they’ve got what it takes to survive.

What are your thoughts on South African theatre today, and what do you consider its achievements and challenges?

It’s ironic that the bad old days under apartheid produced some remarkable work, the so-called protest plays: Fugard’s collaborations with John Kani and Winston Nshona on The Island and Sizwe Banzi Is Dead. Although those pieces were dealing with tragic themes, they were never solemn; they had extraordinary energy and humour. I hope that current South Africa theatre is challenging writers, directors and actors to show as much chutzpah.

Not many people know about your painting and writing. Tell us more about your work in these other art forms?

I’ve published four novels (including Middlepost), three theatre journals (including Year of the King), three plays (including Primo), and my autobiography, Beside Myself. But painting is also playing a major part in my life these days. I’ve had exhibitions at the London Jewish Cultural Centre (2008), the National Theatre (2009), the Sheffield Crucible Theatre and Coventry Herbert Gallery (both 2010), and I’ve been surprised at how much I’ve enjoyed these, and how well the pictures sold. I suspect that painting is what I’ll do when I retire as an actor. Anything else you would like to add? Just that it’s so good to be home again!

Sir Antony Sher is performing Broken Glass at the Fugard Theatre from 22 March to 16 April. Visit www.thefugard. com for more information, and book at Computicket.