Julian Resnick writes from Israel

It was at UCT. I don’t remember the name of the lecturer. I am unsure as to the year (the options are 1973,1974 or 1975). I have no idea what the essay topic was. I do remember it was for an introductory course in Sociology, Soc 1 we called it. I do remember choosing the following quote by Bertoldt Brecht to introduce the essay:

“What a time it is when to talk of trees is a crime, because of all the crimes left unsaid”.

For some reason, possibly because of what I lived through, Apartheid, the First and Second Lebanese wars, the painful (for all) clashes in Gaza, our departure from Gaza, the internal strife in Israel (all parts of our ongoing struggles for a peaceful life), it often felt as if it was inappropriate to celebrate life, to enjoy the many good things, blessings, which have also been a central part of my life. And there have been many here in Israel.

And this feels like another of those dramatic, painful moments. Far away, and yet, like so many far away events that we are shielded from, invading our lives constantly, forcing us to face questions we would rather avoid, a conflict in which innocents die.

Ukraine. Almost no need to add any words to Ukraine.

A mass Akeda perhaps. I am reminded of those powerful lines from Wilfred Owen’s poem written in the trenches in Flanders during the First World War when he reflects on the story of the Binding of Isaac and writes of his own situation:

The Parable of the Old Man and the Young

So Abram rose, and clave the wood, and went,

And took the fire with him, and a knife.

And as they sojourned both of them together,

Isaac the first-born spake and said, My Father,

Behold the preparations, fire and iron,

But where the lamb for this burnt-offering?

Then Abram bound the youth with belts and straps,

and builded parapets and trenches there,

And stretchèd forth the knife to slay his son.

When lo! an angel called him out of heaven,

Saying, Lay not thy hand upon the lad,

Neither do anything to him, thy son.

Behold! Caught in a thicket by its horns,

A Ram. Offer the Ram of Pride instead.

But the old man would not so, but slew his son,

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.

Wilfred Owen

It is uncommon to find the next sentence in a piece of journalistic prose: I hope that when you read this, what I have just written and some of what I am about to write will be irrelevant. I really hope that when you read this, these painful events will be behind us, at least for those of us who watched from afar. (For others, it will never be behind them. It will always be a part of who they are).

But, in spite of the time it is, I am going to spend the next little while visiting an exhibition with you in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Come with me, just for a short visit which I hope will whet your appetites for a real visit next time you are here.

I am going to take you to a really special exhibition of Israeli art. Possibly because of the prohibition in traditional Judaism against graven images, most of the language of early Israeli art is borrowed from Christian iconography which dominated the art of Europe from the Late Middle Ages until a Modern language of art burst onto the scene with the Enlightenment. But now, just over a hundred years since the beginning of an Israeli oeuvre, it is bursting at the seams with imagination and a language of its own, the language of Modern Israeli Art which is part of the extraordinary renaissance of the culture of the Jewish People, one of the wonderful consequences of our regrouping as a People in the Land of Israel.

The opening words at the entrance to the Exhibition are: Material Imagination. Israeli Art. Israeli art and the National narrative are inextricably intertwined. Since its inception, Israeli art has been the visual expression of the old-new Hebrew culture, assigning the Zionist brushstroke a national role. One common thread — even among the contradictory readings of art in Israel — regarded the work of art as an expression of Jewish and Israeli reality, with its ebbs and flows. There seemed to be demand made of Israeli art, whatever medium, to say something — as if a capsule containing a verbal message lay within. (Dalit Matatyahu, Senior Curator of Israeli Art)

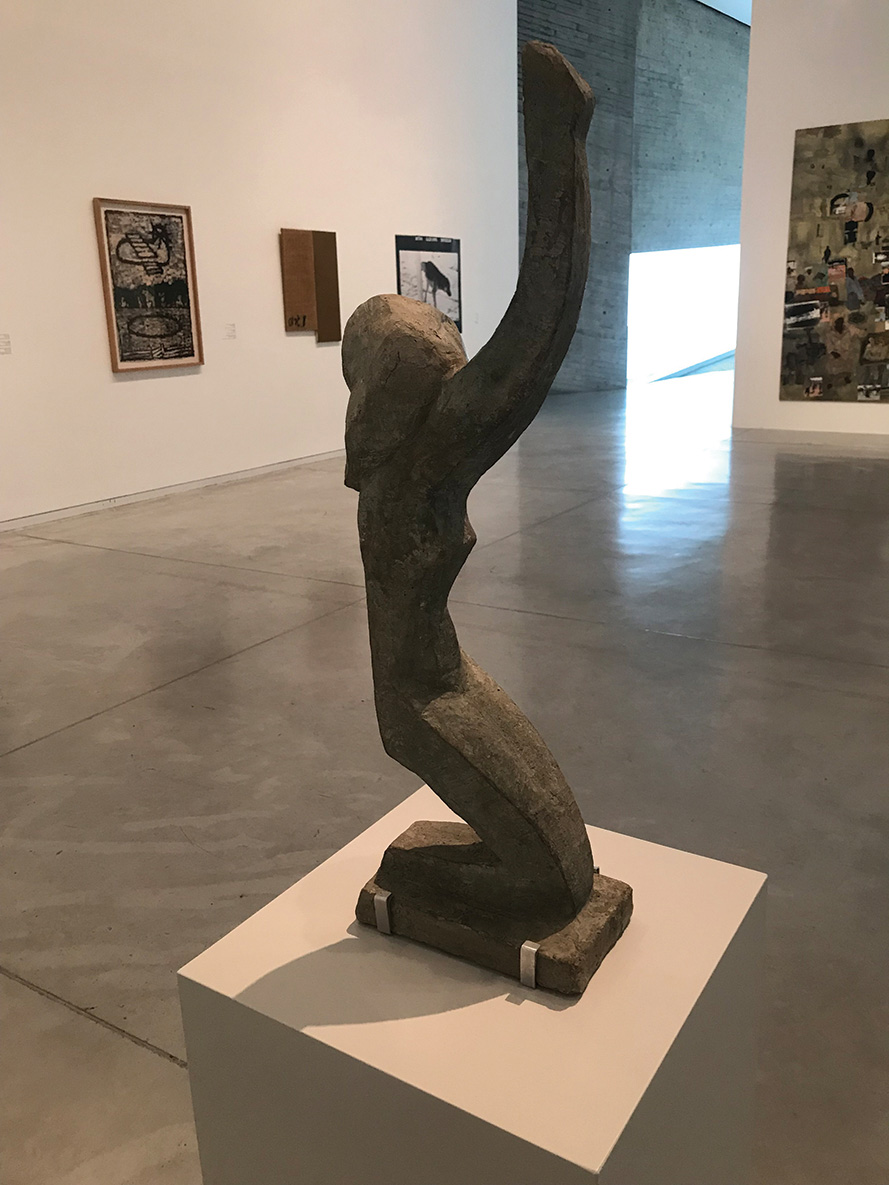

Mrs Harare welcomes us into the exhibition. The sculptor is Chana Orloff, born in Ukraine in 1888, settled in Palestine at the age of 16 (just after my Lithuanian-born grandfather Israel Resnick of Kupershik arrived in Malmesbury to begin farming), studied art in Paris with Soutine, Modigliani and Chagall (notice how the Israeli curator chooses to mention three Jewish artists in Paris at the same time; there is an awareness here of our place within Jewish culture in the rest of the world as well), lives in Tel Aviv until her death in 1969. Who is Mrs Harari? One of the founders of Tel Aviv. An educator and an activist.

I notice the places of birth of many of the artists; Moldova, Israel, Morocco, Ukraine, Poland, Russia, Lithuania, Egypt, South Africa and on and on. This is another part of the story. Our material culture — in the language of this exhibition, our material imagination — was created by the most extraordinary process of what in traditional Jewish terms we call ‘The Ingathering of the Exiles’, that almost messianic description which fits the Zionist movement like a hand to a glove, even though most of the activists of Zionism self-defined as secular (I, by the way, question the notion of the term when it comes to denoting Jewish Identity, but that is another story).

The exhibition is divided into three parts. Enjoy a few of the works of art with me.

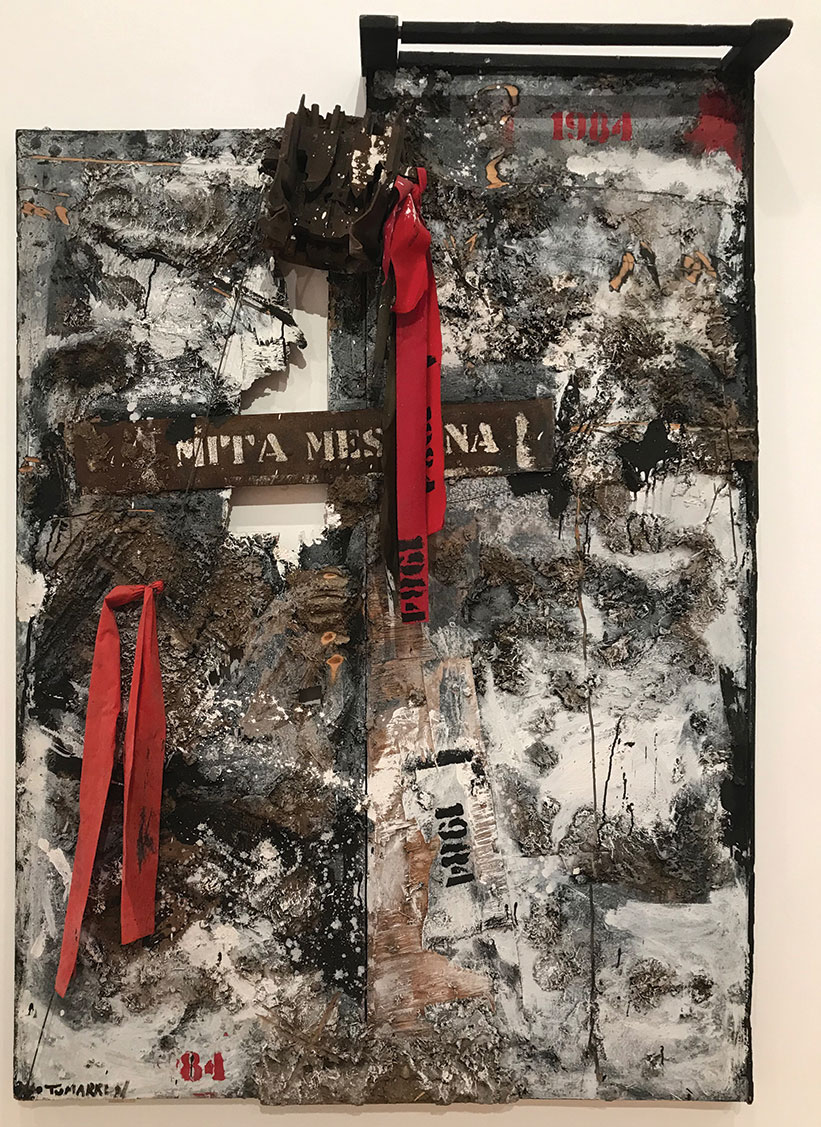

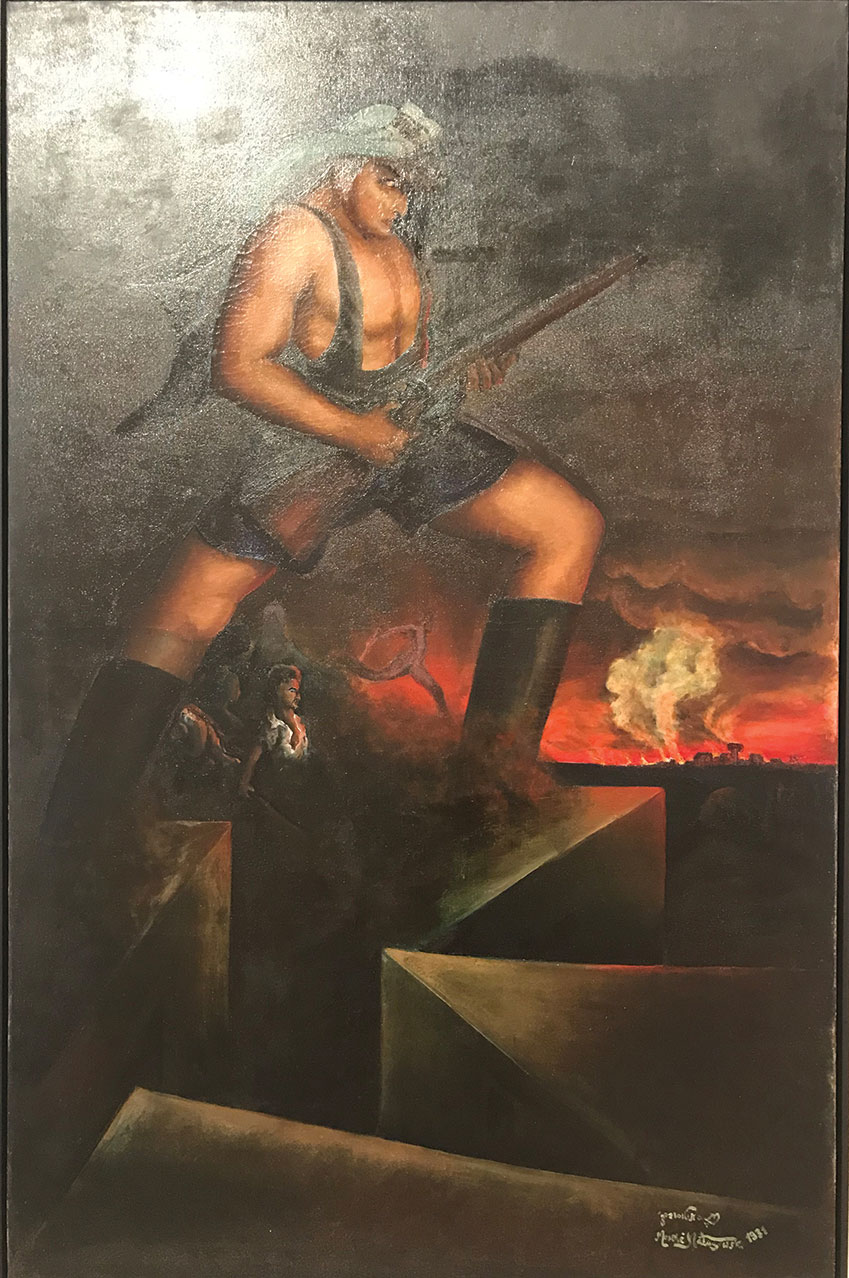

Blazing Movement is the first room. Two works which might represent this room might be either Moshe Matusowkski’s (born in Warsaw) Untitled or Yigal Tumarkin’s (born Dresden) Strange Death.

The second room is named Airship. Two works from here which might represent this section are Gideon Gechtam’s (born Alexandria) Beds, or perhaps Ma’ayan Elyakim’s Snail Knife.

The third room finally has a name you and I might have chosen if we were curating this exhibition — Promised Land (but then of course the content will confound). I have to include a work by one of my favorite Israeli artists, Reuven Rubin’s (born Galati, Romania) Temptation in the Desert, David Reeb’s (born Rehovot) challenging Anemones III or perhaps Moshe Sternschuss’s (born Jezierzany, Poland) Longing.

I have shared just a few of the many extraordinary works which make up this exhibition. I hope you enjoyed them.

Julian Resnick was born in Somerset West and grew up in Habonim Dror. He studied at UCT, and made Aliyah to 1976. He’s conducted numerous shlichuyot and educational missions on behalf of Israel, to Jewish communities in England and the USA. He works as a guide in Israel and around the world (wherever there is a Jewish story). He’s married to Orly, and they have three children and six grandchildren and is a member of Kibbutz Tzora

For more on this exciting exhibition, visit https://www.tamuseum.org.il/he/exhibition/israeli-art-material-imagination/

Published in the PDF edition of the Pesach/April 2022 issue – Click here to get it.

• To advertise in the Cape Jewish Chronicle and on this website – contact Karyn on 021 464 6700 ext. 104 or email advertising@ctjc.co.za. For more information and advertising rate card click here.

• Sign up for our newsletter and never miss another issue.

• Please support the Cape Jewish Chronicle with a voluntary Subscription for 2022. For payment info click here.

• Visit our Portal to the Jewish Community to see a list of all the Jewish organisations in Cape Town with links to their websites.

Follow the Chronicle: Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn