By Tali Feinberg

As Day Zero loomed over Cape Town earlier this year, Dr Solly Lison remembered something: his late brother Joe Lison had practically predicted this crisis when he recorded the Cape’s history of water problems in his thesis entitled ‘From Rivulets to Reservoirs: The Story of Cape Town’s Water Supply from 1500 to the future’, published four decades ago.

“We grew up in Vredehoek, and Joe would climb the mountain, where he became fascinated by the history of Cape Town and its water,” recalls Dr Lison. Joe was somewhat of a genius — after matriculating from Herzlia he studied at the University of Cape Town, then volunteered in Israel during the Six Day War. It was when he returned that he decided to research and write his paper on the Cape’s drought history, spending hours in the archives. He completed it in 1972 after which his mother typed it up, but it was turned down by publishers who said no one would be interested in reading it.

And so it remained in the Vredehoek home where Dr Lison now lives. Meanwhile, Joe decided he wanted to go back to Israel, but was turned down because he had developed Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and was feared to be a burden on the state. He was eventually allowed to make Aliyah at the intervention of Golda Meir, who herself suffered from the disease.

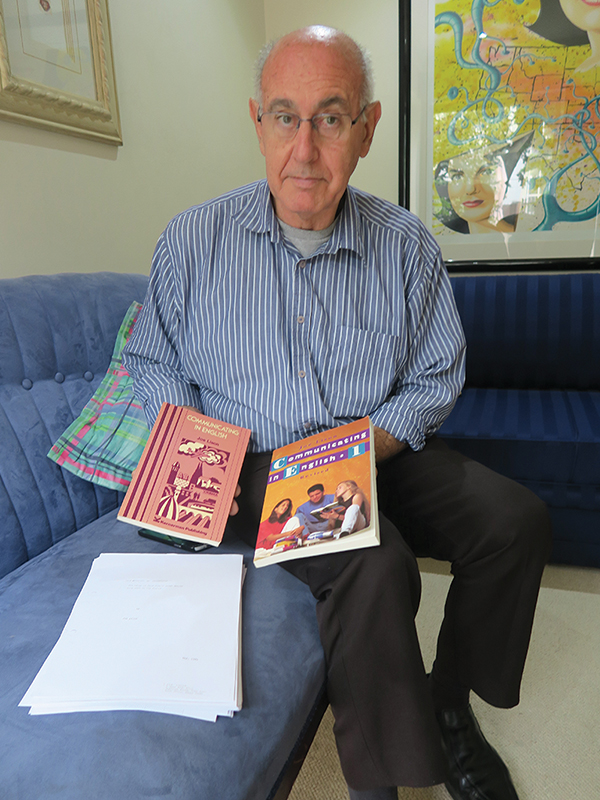

The Jewish State can be greatly indebted to Joe Lison, who went on to write an award-winning English matric textbook that is still used across Israel today. But back in Cape Town, his water thesis remained untouched. Yet the research is startling: He demonstrated that water crises, drought and the strain on water due to population growth have always been the norm in the Cape — not the exception.

“Fresh water was always to be found at the Cape. That was, after all, the main reason for establishing the settlement. Yet from the outset there were water problems. The problem at the Cape is that although rainfall is good, it is confined to the winter months, and for the supply to be available all year round, suitable steps must be taken to store water,” he wrote.

He describes the building of the first reservoirs in 1663, and how water restrictions began as early as in 1761. “During the 18th century, every tiny spring on the sides of Table Valley had been sought out, and its water piped down.,” he wrote.

He records that in 1822, one W.Bird says of Cape Town’s water supply: “A scarcity of [water] is one of the curses of South Africa.” A notice dated 23 August 1826 warned “all persons not to commit any damage against the waterworks, on pain of a fine of 100 rix dollars or being imprisoned for three months.”

His research continues: “During the winter of 1834, very little rain fell, and restrictions were imposed. In April 1835 there was an urgent need for reducing the supply of private water leadings because of ‘the great diminution of the stocks of waters.’ In 1835 the Water Committee resolved to advertise (in the Gazette) the quantity of water stored in Cape Town so that the population should control the use of water and not be surprised if restrictions were imposed.

“In 1840, both shipping and the population were increasing rapidly, and something had to be done to increase the water supply. In 1949 a severe drought reduced the river to a flow of only 2 gallons a minute. The Superintendent reported that the scarcity of water was so great that he had stopped street services, to keep a reserve for fire-fighting. This was followed by agitation to increase the water supply. This led to the reservoir constructed below De Waal Park in 1846.”

It was later that the Molteno reservoir was built. 1880 was a very dry year, and water was still rationed. After many leaks and collapses, the reservoir was finally completed in 1886. Lison goes into great detail about the building of reservoirs on Table Mountain.

1901 was a year of serious drought, and by 1903, Cape Town was so short of water that in summer supplies had to be cut off for certain periods during the day. Years passed, and nothing was done to alleviate the problem, though it was spoken of constantly for about ten years by this time.

1916 was another year of crisis. Restrictions were again imposed, but by May, ‘welcome rain’ fell. Still nothing constructive was done to solve Cape Town’s problem.

A severe water shortage hit the Peninsula after October 1919. By February 1920 the position was becoming critical. The Council was forced to send a letter to all consumers entitled ‘Conservation of Water Supply, calling everyone to ‘exercise the strictest economy in the use of water so as to ensure against a serious shortage before the end of the dry season’ and further water restrictions. People were liable to fines and many private individuals began boring for water on their premises. Still no rain fell. On 2 April, a notice in the Cape Times informed that there was only enough supply of water to last 28 days.

Prayer services were held, in the hope that this would bring rain. On 1 May 1920 an advertisement warned that there was only enough water for 13 days! Two days later the newspapers began to tell a very different story: Welcome rain on 3 May 1920. By 26 May all restrictions were withdrawn. On 24 June the Cape Times reported: “The reservoirs are now full.”

Water crises continued almost every year. Finally, in 1929, a new wall at Steenbras Dam was completed, and from then on there was no shortage of water in Cape Town for 26 years. The city once again experienced water restrictions during the summer of 1949, and in 1952 the Steenbras dam wall was raised again.

In addition, construction of the Wemmershoek Dam near Paarl and Franshoek began in June 1953, as this area had the highest rainfall in the Republic of South Africa. The Voelvlei dam was built in 1971.

Lison’s thesis closes with discussion of the upcoming construction of the Theewaterskloof Dam, and his suggestions for drought-proofing the Cape. “We will be able to stretch supply if some of the water is re-used,” he writes, suggesting that “the re-use of sewage and industrial effluent constitutes a substantial water resource,” and this is indeed done in Israel today. He also writes that “it is probable that the city will be one of the first in South Africa to utilise desalinated seawater.”

Lison concludes: “The important thing is that it takes time to initiate and develop any new ideas. As this story shows, the past history of water supplied to Cape Town is not a particularly happy one —indeed it has proved to be a record in which one crisis followed another. Whatever steps are taken in the future to provide Cape Town with sufficient water, one can only hope that the planners will not repeat the blunders of the past by waiting until too late before embarking on schemes too inadequate.”

Perhaps if Joe Lison had been here today, he would have shouted this warning from the rooftops. Tragically, he passed away on 17 May 1981, the day after his 36th birthday. He left behind his wife Shoshana and one year old miracle baby Gillit, who were supported by the royalties of his bestselling textbook.

“It was voted Israeli teachers’ favourite textbook in 2006, 25 years after his death,” says Dr Lison, who still mourns his brother and how much more he could have contributed to the world.