By Nancy R Krisch

It is important to know where your shoes are, keep your important documents secure, and always tell those nearest and dearest that you love them.

If streets are aflame post bombing, a wet washcloth over one’s mouth is helpful. Also, that one bomb can incinerate your precious possessions, and that photos are essential to memory. My mother once came undone during an air-raid, hysterically crying and screaming. Her mother slapped her across the face and told her to pull herself together, that there was no room for uncontrolled emotion in the bomb shelter. War is not for sissies. Penetrating deeply, its residual effect lasting much longer than eventual cease fire, for generations. Each armed conflict providing the global community with a new batch of victims, lost limbs, splintered families, broken societies and cultural devastation.

I am 60 years old and have been parentless for a long time, losing my father and mother to cancer 33 and 23 years ago. As painful as their deaths were, I felt blessed that they had died of natural causes, and relieved that nothing had happened to me while they were alive. All the eggs had been in my basket and inflicting more pain into their lives not on my agenda. My teenage complaints seemed trivial in comparison to what they had experienced. Though my parents have been physically absent for a long time, the ongoing lessons and penetration of their life experiences, hardship and rebuilding is ever present. I have become increasingly aware of the dimension this added – and took away – from my life, and have greater understanding of their personalities and idiosyncrasies resulting from the tragic trajectory of the family. I remain in awe of their perseverance and strength to move forward, to live their lives and embrace their adopted homeland. All of this in conjunction with balancing family loss, their wounds seared open when records were made public and further details of their loved ones’ fate revealed. The sole survivor of his family, my father endlessly watched World at War on television, searching the footage for familiar faces, his emotional devastation and longing palpable until the end of his life. In his final days, under palliative care, he called out to his mother in German.

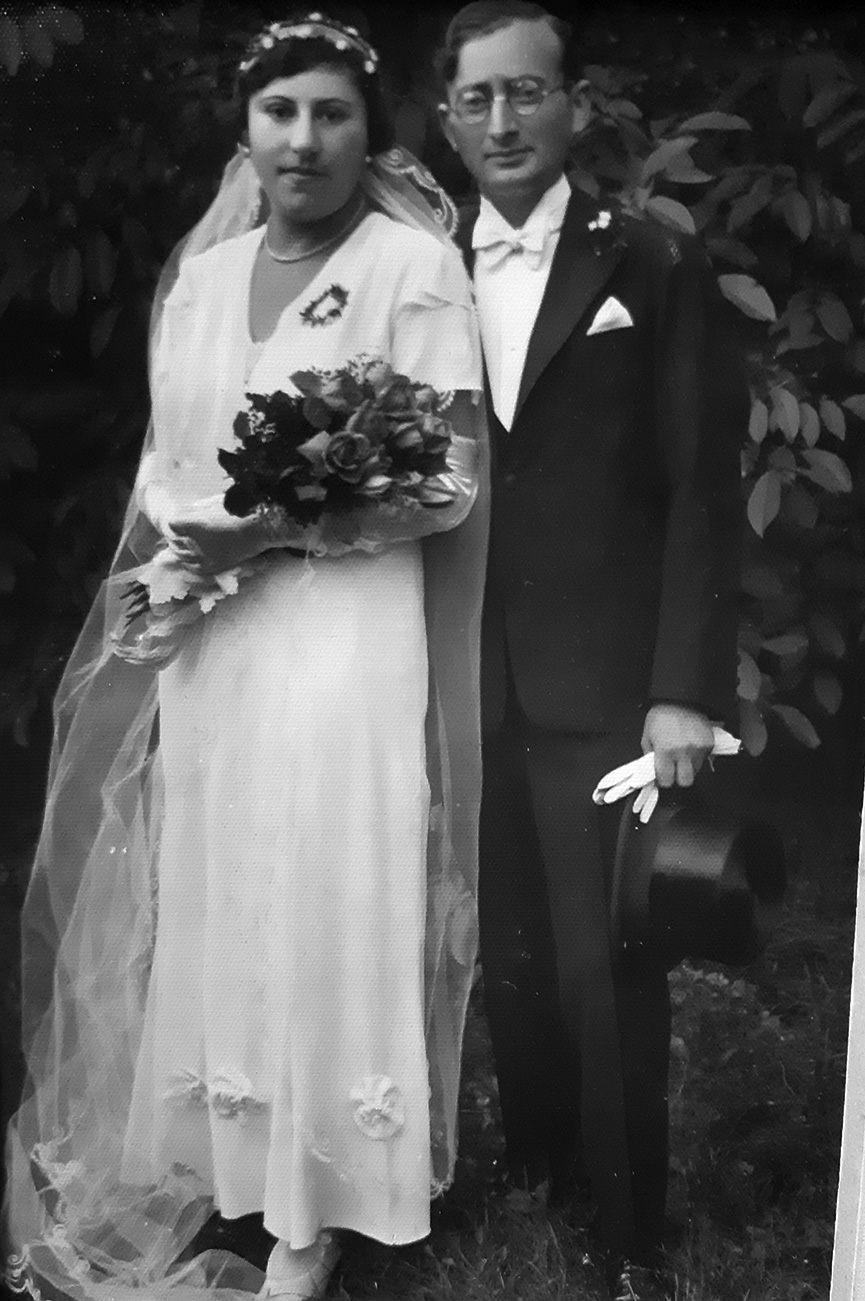

My parents provided for me, their only child, as best they could, though decisions were measured by need vs want and our financial realities. I did not always navigate this easily, as the desire to fit in was intense. There were no swanky vacations, sleepaway camps, designer clothes du jour, or enrolment at the summer college prep academies frequented by my intellectual peer group. No frivolous purchases, and heaven forbid – no blue jeans, wooden clogs or striped clothing. I never questioned growing up in an apartment, sharing a bedroom with my Omi until her death when I was 13, or that the four of us had only one bathroom. Had Omi lived longer, our room-mate situation would have continued until I went to university. In the early days I didn’t ponder why there was no extended family. My parents’ friends were my Tantes and Onkels, and their children my cousins. For a long time, I didn’t know many details. I was fortunate to learn that my parents’ early lives in Berlin were happy, complete with childhood antics and family gatherings. This sequencing of positive family stories first, and normalcy of life, perhaps paving the way for a healthier approach to what would be revealed next. “And then came a man named Hitler,” my mother said during one of her informative story sessions we called ‘Episodes’. I remember trying to digest the information and deal with the veil of darkness that suddenly shrouded my otherwise happy existence. It was unfathomable that my parents and Omi had endured wartime and extensive loss. How could it be that the extended family had all been murdered? I developed a protective shell around these facts, one that would allow me enough emotional distance to keep walking through life without spinning into depressive cycles. My coping style wouldn’t allow me to dip into the profound awfulness of my paternal grandparents, aunt and uncle being forced into cattle cars and taken away, all dead within a year of their deportation. That they lived and died in horrific conditions. Or that Onkel Gerhard, my mother’s brother, was executed by guillotine right in Berlin following his resistance activity and arrest.

It was no wonder that on educational trips to historic areas in the United States I was banned from sticking my head into the wooden stocks used for prisoners. During thunderstorms I would meet my mother in the windowless passage of our two-bedroom flat. While I was just a child trying to escape the flash of light and frightening crack of thunder with closed eyes and hands over ears, my mother was being triggered back to wartime and the shocking explosive sound of bombs and accompanying fire. At 16 I callously announced to my father that I hated being compared to dead people, while he noted my resemblance to his sister. He was but grasping for the connection that my very existence provided, that they somehow lived on in me. I couldn’t deal with it then, but now I too search for resemblance in the few photos I have, comparing them to my own children. These lasting truths born of wartime experience are not easily dismissed, only displaced.

Here we are in 2022, and scenes from the Ukraine have unsettled me in a way images of other conflicts have not. I cannot think about much else at the moment. While I genuinely care about human beings regardless of who they are, and am deeply disturbed by suffering in all parts of the world, the plight of the Ukrainian people is impacting me differently. A recent Facebook post in the Children of Holocaust Survivors group exposed that I am not alone. Someone posted about what she was feeling, seeing the images out of Ukraine, and the triggering that was happening. The comments poured in, including my own. We children and grandchildren of war victims, scattered across the globe but unified by our collective loss, were feeling it simultaneously. This is the ripple effect of war – the inherited trauma, whatever you would like to call it. In my need to devour information about who was doing what to help the Ukrainian people, I discovered that Limmud contacts living in Poland had opened their home to a refugee family. That the young Ukrainian woman started a grassroots effort. A veteran combat medic, she was amassing supplies for her husband and fellow Ukrainian resistance fighters on the front line. All I could think about was my uncle Gerhard, refusing to leave Berlin, taking on an assumed foreign name, living on the streets, his stolen gun in hand… One must support people on the ground, or else count oneself amongst those who decide things are simply not bad enough to garner proper intervention. The story is too familiar and the resulting impact of looking the other way too raw. As Jews we know this well, as humans we have an imperative to act in whatever way we can.

The trauma caused by intolerance and the deep hunger for power and authority is far-reaching. Understanding the residual impact of trauma, and untwisting the psychological damage caused, yields greater acceptance, tolerance and understanding of the other. This is hard work, and those willing to dig deep into their psyches are few and far between. Without the necessary internal work, the stunting and vicious cycle that intolerance birthed by pain brings forth continues and, I believe, is why history repeats itself. The intergenerational pain that must be endured with each successive atrocity is costly on every level. It should be noted that these effects are not exclusive to war, but oppression and marginalisation as well, with no guarantee for true healing.

The experiences of my family have instilled resilience and given me an understanding that nothing is permanent and that one should not get too comfortable with the notion that tomorrow will be the same as today. Unless we work hard to heal the ills of our respective societies and help to uplift and ‘see’ each other – these will continue to be the unfortunate realities of living in our world. No matter how privileged and protected we believe ourselves to be, tomorrow we may also need to know where our shoes are.

Nancy R Krisch is an expat American who has called South Africa home for the past 16 years. She is a dedicated community organiser and has held various leadership positions in Wynberg-based organisations and within the Jewish community. Nancy enjoys writing, and is deeply touched by human interest stories and the resilience of people. The mother of two US-based adult children, she lives in Wynberg with her husband Tony Lachman, a returning South African.

Published in the PDF edition of the Pesach/April 2022 issue – Click here to get it.

• To advertise in the Cape Jewish Chronicle and on this website – contact Karyn on 021 464 6700 ext. 104 or email advertising@ctjc.co.za. For more information and advertising rate card click here.

• Sign up for our newsletter and never miss another issue.

• Please support the Cape Jewish Chronicle with a voluntary Subscription for 2022. For payment info click here.

• Visit our Portal to the Jewish Community to see a list of all the Jewish organisations in Cape Town with links to their websites.

Follow the Chronicle: Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn